The Oregon Environmental Quality Commission voted to approve the Advanced Clean Cars II Rule at a special meeting December 19th. The rule is based on vehicle emissions standards initiated by California.

Featured Post

This is the Kodak Moment for the Auto Industry

Plug-In Drivers Not Missin' the Piston Electric vehicles are here to stay. Their market acceptance is currently small but growing...

Thursday, December 29, 2022

Oregon Joins West Coast Gas Car Ban

The Oregon Environmental Quality Commission voted to approve the Advanced Clean Cars II Rule at a special meeting December 19th. The rule is based on vehicle emissions standards initiated by California.

Tuesday, December 27, 2022

Powerwalls and Power Outages

Look at the map above. This is the region where I live. More than 55 thousand people here are currently without power right now. We had an Arctic blast blow through with snow and ice last week and this week there's a wind storm taking out branches and trees. To pile on to all of that, there's domestic terrorist movement that somehow thinks that attacking electrical substations will manifest their extremist political agenda.

Tesla Powerwalls don't have a "grid under attack" setting (yet).

There's no good time to lose power, but during a winter storm is the worst. Without power, you cannot run your furnace to stay warm. This is true even if you have a gas furnace because power is needed to run the fans and control systems. If you opt to evacuate to stay with friends or family or to check into a hotel, the road conditions can make travel difficult. These storms and outages can be deadly.

Powerwall to the rescue

Saturday, December 24, 2022

Solstice, Storms, & Solar - Tesla Powerwall: StormWatch vs VPP

Unstoppable Meets Immovable

|

| Powerwall Discharging While in Storm Watch Mode |

Solstice Energy Use and Production

Ω

Sunday, December 11, 2022

Tesla Semi: Another "Impossible" Achievement

Why Electric Class-8 Semi-Trucks are 'Almost' Impossible

As we discussed in this article, Musk and Co. focus on the Class ½ Impossibilities. These are the things that are physically possible but at the edge of our technical know-how. Class ½ Impossibilities have just been enabled by technological advances, either directly or by advances in tangential areas that can be applied with other optimizations. These are not easy to achieve, they require breakthroughs, optimizations, hard work, and some luck. When completed, these enable something that we've never seen before and therefore something which many people will say is impossible.

An Elephant That Moves Like A Cheetah

The Tesla Semi has three Tesla carbon-wrapped Plaid motors. Musk described the vehicle as a beast. He said it's a giant Semi, but unladen, it moves like a sports car. He went on to say, "It's like watching an elephant move like a cheetah."

Tesla's "Impossible" Achievements

One Roadster: When Tesla started, the founders often heard things like, "This is a fool's errand. Nobody wants an EV. They are slow, there's nowhere to charge them."

The Roadster showed that EVs can be sexy and fast. In the quarter mile, this electric car would blow away gas cars costing 10 times as much. It changed the perception of EVs. But the nay-saying continued, "A few Silicon Valley millionaires and billionaires will buy them, but no one else is interested (or can afford) an EV."

Two Model S: The Model S disproved the "only in Silicon Valley" narrative. Tesla had sales around the world.

Three Supercharging: Tesla's Supercharger network is impressive. There are currently more than 40,000 Superchargers installed around the world. These have high availability and locations near major travel corridors. This is vital infrastructure for electrified transportation.

Four Energy Storage: Vehicles are just part of Tesla's business. Tesla's Megapacks have 3.9MWh of capacity. This is enough to run the average home for over 130 days. Gang these together and you can make an impressive installation like the 730MWh Elkhorn Battery Energy Storage System in California or the 600MWh Arroyo Solar Energy Storage in New Mexico. As I write this in late 2022, Tesla has 5GWh of Megapacks and Powerpacks installed or under construction.

Before we had significant energy storage, the amount of renewable energy that could be placed on the grid was limited. The legacy fossil fuel generation of the grid could not handle the fluctuations that wind and solar caused. However, with renewable sources buffered behind a battery pack, all of those fluctuations are washed away. The grid, instead see a steady, adjustable rate from the batteries that can be dialed up or down in milliseconds to support the grid exactly as it needs, exactly when it needs.

Tesla's semi is the most recent on this list, but it won't be the last.

This is The Beginning - Commence Iteration

Wrapping It Up

Friday, December 2, 2022

How Big Is The Tesla Semi-Truck Battery Pack?

Tesla delivered the first of their semi-trucks to a customer last night. The Pepsi / FritoLay company was the lucky customer. We learned a lot about the vehicle's capabilities in the presentation, but one thing we didn't learn is the size (energy capacity) of the battery pack.

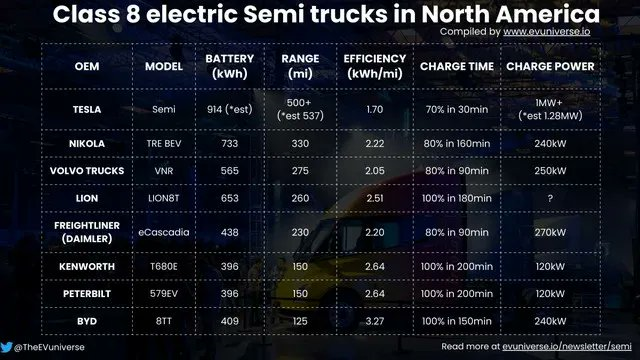

In this entry, we'll use what we know about the battery to put upper and lower bounds on the capacity and infer a likely size. If you don't want to read to the end, our current estimate for the size of the battery pack in the Tesla Semi is 914kWh usable. Read on if you'd like to know how we came to this conclusion.

We know the cells are produced at Giga Nevada and, given the hauling use case, they are likely the high-Nickel chemistry that was developed in partnership with Panasonic.

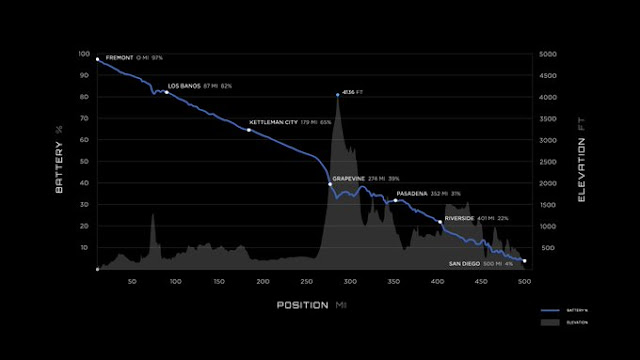

Tesla has said that the semi (fully loaded) has an efficiency better than 2kWh per mile. Additionally, the semi recently completed a fully loaded 500-mile drive.

Using these two numbers gives us a 1000kWh (1GWh) capacity estimate, but there's more to the story.

Taking a close look at the drive above, you can see that it started with 97% charge and ended with a 4% charge; so if you were doing a true 100 to zero percent trip, you'd have another 7% of capacity to use. That would be a 537-mile range, at 2kWh per mile, the upper bound for the pack size is 1,075kWh.

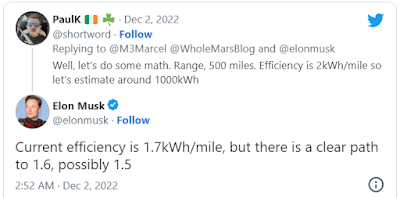

As Musk often does, he gave us more info on Twitter. Specifically, he said that the current efficiency of the semi is 1.7kWh per mile. Another digit of precision would be nice, but we'll go with this for now.

Recalculating using this number and the 500-mile trip yields an 850 kWh battery. Using the inferred 537-mile trip would use a 914kWh capacity battery pack usable.

In battery-powered electric vehicles, there's usually some reserve capacity that's locked away from the driver's use. This helps extend the battery lifespan. If we assume a 6% reserve, this adds another 55 kWhs to the pack, bringing the total pack size to 969kWh.

A 1.7kWh/mile efficiency is the energy equivalent of about 20 miles per gallon (20 MPGe while hauling a full load). For a comparison, with a full load, Diesel class 8 semi-trucks average about 6 MPG. The most efficient Diesels semis out there (the Freightliner Cascadia Evolution) gets 10 MPG on a good day. So the Tesla Semi has a fuel efficiency that's triple the average (and double the best), compared to Diesel semi-trucks.

Today, semis are primarily Diesel-powered. Electrifying semi-trucks is very important. In the US, they are only about 1% of vehicles on the roads, but they have a very outsized pollution impact; they generate about 20% of vehicle emissions and about 36% of particulate emissions. This directly has an impact on health and air quality. Semi-trucks from Tesla, Freightliner, BMW, and others will help make a cleaner world.

Monday, November 28, 2022

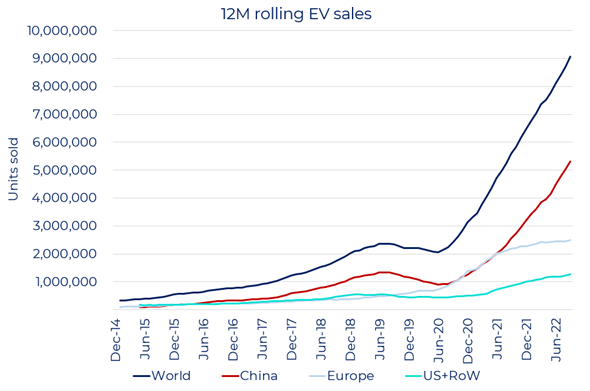

EVs On Brink of Mass Adoption

|

| Source: Guinness Global Investors |

Saturday, November 12, 2022

Why Tesla's Charging Network Should Become Everybody's

|

| The fractured fast charging market: CHAdeMO, Tesla, SAE Combo (CCS) image via chargedevs.com |

Charging is an important part of the EV ownership experience. If you have a living situation that allows for it, charging up at home is very convenient. It only takes seconds to plug in and your car starts out each morning fully charged, ready to take on the day. When you're on a road trip, things are different. You have to use the public charging network to fill up and keep rolling. This could be charging overnight at a hotel or roadside fast charging.

Up to this point in time EVs have been less than 1% of new vehicle sales. This means that they have been purchased by the portion of the market that is the most enthusiastic about the technology. These early adopters have generally been content (perhaps even excited) to hunt for charging stations and to mold their drives around the available infrastructure. As EVs move to mass adoption, this tolerance quickly fades; it will be important to have a vast, easy-to-use, reliable, fast charging network.

When considering public EV charging network infrastructure, you must look at several factors (speed, reliability, availability, access, usability...). Looking at the three fast charge networks (CHAdeMO, CCS, and Tesla), considering all of these factors, in our previous post we concluded that (although there is room for improvement) Tesla is the only charging provider that is currently offering a robust positive charging experience. Tesla has well-positioned charging sites; no membership sign-in, apps, or cards are required to initiate a session; there are multiple stations per location; the stations are fast and operational; and there is usually no waiting (at most locations).

Tesla has offered to allow other automakers to use their network. In 2015, Elon Musk said, “Our Supercharger network is not intended to be a walled garden. It’s intended to be available to other manufacturers if they’d like to use it. The only requirements are that the cars must be able to take the power output of our Superchargers, and then just pay whatever their proportion their usage is of the system.” This statement from Musk is aligned with Tesla's goal to accelerate the advent of electric transport (not just Tesla's cars).

To date, no automakers (that I am aware of) have taken Musk up on this offer. Should they? Below we'll explore what this partnership might look like.

|

| Porsche's proposed 800-Volt fast charger |

Proprietary Versus Standard(s)

Which fast charging type to choose?

If you were the head of a new EV program at a car company (such as one of the many new EV startups or a conventional car company getting into the EV market), you would have to determine which of the fast charging solutions you would choose for your upcoming line of EVs. The options are:- Design your own proprietary solution

- Select the Japanese standard (CHAdeMO)

- Select the SAE standard (CCS)

- Partner with Tesla

Proprietary Solution

Option 1 has several drawbacks. It has a large capital requirement. You would need to build out a vast network in all regions where you sell vehicles. It's a multi-year effort. Porsche has stated that they have engineered an 800 Volt fast charging system. If Porsche were to deploy yet another network, this would further splinter the industry. Porsche has a great record of innovation, they would be better off working with one of the groups in options 2, 3, or 4 to improve charging for all. Considering the cost and effort, let's consider this a DOA option, listed only for completeness.Standards-Based Fast Charging (CHAdeMO/CCS)

Option 2 or 3 utilize existing public networks. This is what most non-Tesla automakers are selecting. Here it is important that you consider the experience that your owners will be subjected to. Simply selecting a CHAdeMO or CCS port for the car and then saying "fueling infrastructure is someone else's problem" is a poor option. Automakers must become involved with the charging standard organizations. This should include investments into the infrastructure network, in the charging provider companies (AeroVironment, ChargePoint, ABB,...), and perhaps even a seat on their board promoting reliability and a positive driver experience.Automakers cannot simply put a fast-charge port on their cars and call it done. The charging networks that support these vehicles and their customers are an important part of the ownership experience.

As we covered here, CHAdeMO seems to be losing steam. If you are considering this option, CCS looks like the better long-term choice. However, there is one more option to consider first.

The Tesla Network

Option 4 is to partner with Tesla. Let's continue with our analogy that you are in charge of a car company's new EV program. Should you partner with Tesla or select CCS? Let's assume you've decided to partner with Tesla. For the rest of this article, we'll explore this option.Justification: Why Automakers Should Take Up Tesla's Offer

Compared to CHAdeMO or CCS, Tesla's network is more complete, robust, and reliable. The network is better planned and positioned, there are multiple stations per site, and no membership card or app is needed to initiate a session. As an EV driver, it is a better experience.Selecting Tesla would give your fledgling EV program an incredible jumpstart and your EV program an incredible innovation partner. This will keep your vehicle's charging technologies on the leading edge. Tesla has announced plans to vastly increase the charging rate of their network in 2017 with Supercharger V3. They also plan to install solar canopies and onsite energy storage. If you are hoping to attract environmentally conscious customers, these (soon to be solar powered) charging stations are a compelling story.

How Would A Partnership Work?

Since no automaker has yet taken Tesla up on this offer, we don't know exactly how it would work but Tesla has laid out some of the framework. Musk has stated that the contribution to the Supercharger network would need to be proportional to use of the network. So, if your company's cars make up 5% of the network's use, your company would need to pay Tesla for 5% of the network's operating cost.Considering the recent changes Tesla has made for idling fees and limited free charging, I'm sure that Tesla would require similar fees for other automaker's vehicles joining the network. These changes were not profit motivated, they were intended to improve network availability. Any car that is blocking a spot is a problem, regardless of the brand, so these rules would likely apply to partner company vehicles too.

As a partner, fees above and beyond the Tesla minimums would be at your discretion. Tesla has said that they are not trying to make a profit from the charging network. However, other automakers would be free to try other models. The fees collected, if any, could be used to offset the payments for your company's portion of the network operating cost.

Additionally, if your company established charging stations and added them to the Tesla network, the Tesla owner attendance could additionally offset the use of your vehicles on the Tesla network. Having this as an option is nice. If the EV project at your company is small, the network use will also be small and the payments to support the network would be negligible. If, however, the fledgling EV program at your company flourishes, then establishing your own Tesla-compatible charging stations in high-use areas can offset the charging events by your cars at Tesla branded superchargers.

Competing?

If your car company is using Tesla Supercharger stations, would your vehicles be seen as competing with Tesla vehicles? Yes. If you are building a long-range electric vehicle, then your car is competing with Tesla, whether or not you are using their network.Partnering with Tesla on charging standards puts you on equal grounds in this arena. This means you will need to make compelling vehicles.

Overcrowding

There has been overcrowding at some Supercharger locations in California and Norway. Tesla is actively installing and expanding their network. More locations will only help if the network growth outpaces new vehicle sales. Tesla has a large number of Model 3 pre-orders. They plan to deliver a lot of cars in 2017 and 2018. Overcrowding is a risk. The changes Tesla has recently made to eliminate free supercharging and to add an idle fee are steps to ensure that the network is not abused and only used when it is needed. Additionally, doubling the network size in 2017 to alleviate congested areas. We'll see if these measures help.The Choice Is Yours

Which "little monster" (as ChargePoint called them) will you choose? If you are a car buyer, this choice will impact where you can charge. If you are an automaker, this choice (among many others) can determine if your sales continue to grow, or if they flatline.Sunday, November 6, 2022

We Need 300 Mile EVs!

Over the years, we've owned 5 EVs in our household. Three short-range and two long-range. They each filled a need, we'll discuss the pros and cons and maybe help you figure out what's right for you.

Ed Says You Don't Need 300 Miles of Range

In an opinion piece in the NY Times, Ed Niedermeyer makes the case that short-range EVs are adequate for most drives and that almost no one should buy a long-range EV. The argument goes something like this:

The average American drives about 40 miles per day and 95% of those trips is 30 miles or less. For the rare time that you do need to take a road trip, you can rent or borrow a gas car. The article goes on to say that you can further supplement your personal transportation with public transportation, micro-mobility, biking, walking, and the like.

Culturally and from a policy perspective, the long-range car is a sledgehammer, the article asserts. Cars have too often been the default assumption and this has choked out the alternatives. Electric vehicles are headed down the same road as their internal combustion antecedents and we can do better this time.

Electric vehicles are an important part of our transportation future. Currently, EVs are battery cell constrained. If short-range EVs are made, rather than long-range EVs, this has two benefits; one, you can make more EVs; two, the vehicles will be more affordable.

The above is a very short paraphrasing of the article. I've tried to steelman (not strawman) his arguments. If you've read the article and think I missed an important point, please let me know.

What Ed's Missing

Ed's article is factually accurate, logical, and completely wrong. Here are a few of the things Ed seems to not understand:

1) Averages Don't Tell The Whole Story

"The average American drives about 40 miles per day."

Have you ever heard the phrase, "If your feet are in the oven and your head is in the freezer, then your average temperature is just right"? Looking at an average is far from seeing the complete picture that the dataset paints.

Maybe you drive the kids to school, then daycare, the gym, work, then grocery shopping and other errands, then back to school and daycare for pick-up time... each of these trips in itself is short, but let's say you don't have charging infrastructure at these interim locations. That means, from a battery/charging perspective, this is a single trip. In fact, it's worse than one long trip of equal distance; if the weather is hot or cold, you'll be cooling/heating the cabin from scratch for each trip rather than getting it to a comfortable temperature and then just maintaining it as you would on a single drive.

Another way an 'average' might hide data: Are there people that drive less than 5 miles (or even zero miles) most days? There certainly are some. How do they impact this average? For a simplified example, let's say you work from home and most weeks you only drive on Sunday when you shop for your elderly mother and take her groceries for the week. This is a 200-mile round-trip drive. Calculating an average, this could (incorrectly) be interpreted to say you drive 200 miles a week, 200 miles divided by 7 days in a week, that's less than 30 miles per day.

A trip average is not the complete picture of how someone uses personal transportation. It flattens the data and removes important nuances that really matter for practical considerations. It's far more important to look at your real-world needs, not just averages.

2) Emergencies

The second case Ed seems to be overlooking is emergencies. If your only personal transportation is a short-range EV, this might not work well in an emergency. Let's go back to the parent running midday errands. If they only have a short-range EV and late in the afternoon most of the range has been consumed, they are about to head home and charge, then an emergency happens. Now they have to pick up a child or head to the hospital... depending on when this call arrives, they may not have the needed range.

Fast charging can fill in gaps, however, short-range EVs frequently do not support DC fast charging. This means for short-range EVs, quick charging is often not an option.

There are other emergency situations too. If you need to evacuate from an area due to an all too common natural disaster, a lack of range (and fast charging) can be a significant problem.

I'm also going to put Detours in this emergencies bucket. Occasionally, you encounter a downed tree, a crash on the highway, or something else and you have to take an unplanned detour. These can add miles to a route and can disrupt the charging plan you had at the start of a trip. Having extra range in this situation is reassuring.

3) HVAC Use and Winter Driving

If you want to heat or cool the cabin in a car, this requires energy. In an EV, that energy comes from the battery pack; the same battery pack that's used to move the car around from point A to B.

EVs use things like heat pumps to efficiently heat or cool, but it doesn't come for free. Compared to an internal combustion engine, there's no "waste" heat that can be recovered to warm the cabin. In an EV, this heat has to be explicitly generated.

Cold temps can be a triple whammy too. When it's cold, batteries don't perform as well and your range is reduced. A study by Consumer Reports showed that EVs only have about three-fourths of their range at 16F compared to 65F.

In the winter, you may be using winter tires. These have better traction in the cold wet snowy conditions, but they increase the energy used per mile compared to the low rolling resistance tires usually equipped on EVs.

For our third and final winner whammy we have running the heater. When you have a small battery packet, HVAC usage can quickly become a significant percentage of the energy consumed. Here's a summer example of HVAC use with our Spark EV:

In the above drive, on a relatively mild summer day, more than a third of the energy used was for climate settings (3.6 kWh out of 10 kWh).

4) Geography

The rule of thumb is that every 1000 feet of elevation gain uses about 10 miles of range. This is more of an issue in some parts of the world than others. Driving around here, we have the Cascades and the coastal range, so elevation changes are common. To know if this will impact you, you'll need to know how hilly your area is. A drive that says it's X miles on Google maps might use more energy than you expect once elevation changes are taken into consideration.

5) Infrastructure

EV infrastructure is not evenly distributed. If you live in southern California, you can likely find a place to plug in when necessary. That might not be as true in Thief River Falls, Minnesota. The ability to charge up mid-day, where your car is parked, makes a big difference. If you can plug in and leave every venue where your car is parked with a full battery, this makes a short-range EV much more viable.

6) Battery Degradation, Long-Range vs Short Range

Most Lithium-ion battery chemistries prefer shallow cycles; that is using less than a full charge. If you can use just the middle third of the battery (avoiding full charges and deep discharges), this will contribute to a much longer battery lifespan.

When you have a large battery, it's easy to keep the battery charge level within that middle third zone for daily driving. However, with a short-range EV, you'll likely be charging to full, daily (or nightly) and deep discharges are far more likely with a small battery pack than with a large pack. So small battery packs lead a harder life.

As long-term readers will know, I tracked the battery degradation of our Nissan LEAF and our Tesla Model X. I (very unfairly) compared the battery degradation here. The thermal management of the LEAF was an obvious contributor to this.

For another comparison (both with liquid cooling), let's look at two cars in our driveway today, a Tesla Model X and a Chevy Spark EV. Both are model-year 2016 vehicles, so they've seen a few years and miles, so we can see how the degradation has progressed.

When new, the Chevy Spark EV had a pack with 19 kWh of capacity. Today that car has 17.2 kWh available. That's a 9% degradation in 6 years.

The Model X on the other hand started with 85.4 kWh and today it has 77.5 kWh. That too is 9% degradation over the same time period. The Model X has also been driven about 20 thousand more miles during this time and it has been Supercharged dozens of times, whereas our Spark EV has no DC fast charging capability.

Smaller battery packs are more often deep cycled, as a result they often degrade faster. If the Spark EV had a similar number of miles as the X, it would be further degraded.

Even in this best-case example of only 9% degradation, the impact is more significant to the shorter-range vehicle. The Spark EV started out with an 82-mile range. Losing 9% brings the range down to 74.4 miles. If your daily usage, including HVAC use and hill climbs, needed 80 miles of range, this degradation could mean the difference between a successful trip or not. Whereas, if you had a long-range EV, with more range than you typically use, you generally have range to spare.

There's A Place For Short-Range EVs

I've painted a pretty bleak picture of short-range EVs. If you have a 10-year-old EV, with 12% degradation and you are driving it in a cold, hilly, region with little-to-no charging infrastructure, you might not have a great EV ownership experience. However, I don't want to say that short-range EVs don't have an important role to play, I just want to clarify that they are not the vehicle for all situations. If you have the right expectations for them (more on this later) they can be great.

The Case For Big Batteries

Nearly all the shortcomings of a small pack are not an issue with a large pack. Having more range than you need, means you have capacity when you need it. This extra capacity means the car is still usable in the winter when the range is reduced and the heater has to work overtime. This means you can take an unexpected detour or drive when an expected event pops up. It also means the vehicle will still have a viable range even when the pack is a dozen years old.

If you live in an apartment building, you might not be able to plug in overnight, this could mean that you have to go to a charging station to charge up. A large battery could mean you only have to go to this charging station once a week instead of nightly. This means less congestion at the (in some regions) all too rare charging infrastructure. That big battery also means that you'll be able to charge at a higher rate (more cells allow the charging load to be more distributed).

Next on our list of big battery benefits is futureproofing. A long-range EV also gives you futureproofing. What if you get a great job offer tomorrow, it's your dream job with more pay, but the commute is 50% longer. So even if a short-range EV is a good fit today, you don't know what twists life will throw at you tomorrow.

Big batteries are not without downsides; they cost more and they weigh more. So what's the right size pack for you? It's the one that fits your needs and expectations (I promised to get back to expectations, so let's do that now).

The Rock Ballet

Let's say you have tickets to a rock concert. The night of the event is here, you have your black band t-shirt on and you're excited to rock out. Then you arrive at the venue; the band you are looking forward to seeing is not there. Instead of a rock concert, they put on a ballet. This would be a huge disappointment and you'd want your money back.

What Does Ed Know?

|

| Twitter exchange with Ed Niedermeyer |

Ed's Bias

Wrap-Up :: It's Up To You

Above, I made the case for big batteries, but I'm not saying that you should buy a long-range EV. Rather, the point is that there are use cases for which long-range EVs fit very well and others where short-range EVs fit very well.

No one knows your transportation needs better than you do (not me, not Ed). You are the best person to decide what would work best for you. Do you live in an area where public transportation is available? Do you have a commute where an e-bike would work? Do you have easy access to a long-range car that could fill in if you need it?... All of these are big factors in making a choice that best meets your needs and no one, not an (uninformed) opinion piece in the NY Times or some blog on the internet should tell you what you should do to meet your personal transportation needs.

Disclosure: I am long Tesla

Sunday, October 23, 2022

Can You Hate Musk and Love Tesla?

I recently posted a story called "No Good Choices" about a friend who's shopping for an EV and he has dismissed Tesla as an option because he "does not like Musk's shenanigans on Twitter." During the discussion, I started defending Musk and it seemed like this was just causing a backfire effect, making him to further entrench in his disdain for the man. Clearly, a different tactic was needed.

This got me wondering, how many other companies does he apply this "do I like the CEO" metric to? Does he research the CEO of Coke or Pepsi before having a cola? Does he look into the actions of Frito-Lay's president before eating Doritos? Probably not, but he's not required to do so.

Musk has leveraged his position to obtain a level of fame that few CEOs have achieved. This public image is, however, a two-edged sword. Combine this notoriety with Musk's unapologetic insolent Twitter persona and he is going to rub some people the wrong way.

So how did we get here?

I would argue that a personality like Musk's is the only type of leader that could have pulled off taking Tesla from zero to the big success that it is currently. A decade ago, Tesla's success was far from assured. It takes someone as stubborn and insolent as Musk to keep moving forward with a vision while the majority of the experts are saying that it is impossible and it's doomed to fail. When the experts repeatedly say there's no demand, when suppliers won't return your calls, when you have to risk your entire fortune to make payroll and build parts in-house because there's no other way to get completed cars out the door, you have to be obstinate to your core. When this was a requirement for success, to now expect Musk to be a "chill normal dude" is unrealistic. The trials that Tesla has faced nearly guarantee that the person at the head of the company will be obdurate.

This is not to excuse his behavior or to dismiss how some people may feel about his tweets. So what to do about the people that are triggered by Musk's online persona? Just give up on them? No. Anyone shopping for a car (or anything else), should buy a product that will meet their needs and bring them joy. If buying a Tesla would make someone feel like they are endorsing things that Musk has said that they don't agree with, then a Tesla would not bring them joy and they should buy something else. There are plenty of other people willing to buy Tesla's vehicles and there are EVs out there from other car companies that need customers too. However...

I'd like to present the case that anyone shopping for an EV should buy the product that best fits their personal needs. Regardless of the company's history or the leadership. It is perfectly fine to buy a Tesla and disagree with Musk. Despite what you may have heard (and the behavior of some owners), it is not. a. cult.

When you are shopping for an EV, look at your budget, your requirements for range, passenger room, cargo space, recharging time, charging locations/network, performance, style... and then buy the car that best fits your needs and budget; Tesla or not.

Should you avoid buying an EV from Volkswagen today because of the company's role in WWII or because of Diesel-gate? I'm sure there are people that avoid VW for these reasons and others. However, I would argue that buying an EV from VW is encouraging them to do the right thing going forward. It helps them put their Diesel products into their past. Look closely into any large company and you'll certainly find blemishes.

The real problem, IMHO, is not what someone tweeted yesterday, but our worldwide use of fossil fuels. Any EV placed in service today is one gas car off the road. As more and more renewable energy sources are added to the grid, these EVs become powered by those renewable sources. The transition of the world's vehicle fleet will take decades. We need to move quickly to a future free from fossil fuels. The transition of the world's electrical grids to 100% renewable will take decades. These decades-long transitions are time that we may not have to avoid the worst impacts of climate change. I find the fretting about who tweeted what about who to be rearranging deckchairs on the Titanic as it's sinking.

Saturday, October 15, 2022

Electric Vehicles "No Good Choices"

A friend of mine is a longtime Saturn car fan. He's currently in the market for an EV. The Saturn badge has been defunct for over a decade, so that's not an option for him. I pointed out that Saturn was a GM brand and asked if he had considered other GM EVs. He said Saturn was not just another GM brand, it was special and his love for Saturn doesn't extend to Chevy or the other GM badges.

Since he's shopping for an EV, we noted that Saturn has a special place in the history of electric vehicles; in the late 1990s, Saturn dealerships sold leased and delivered the GM EV1.

The GM EV1 was the vanguard of the 1990s EV generation (but that ended poorly).

Given this history and his love for the Saturn brand, his wish is that GM would bring Saturn back as an electric-only brand. This is an interesting idea, but unfortunately for him, it seems very unlikely.

Since he wants an EV soon (and a Saturn EV is not an option), I asked him, "What car are you going to buy?" His response surprised me.

He said something to the effect of:

There are no good choices.

I don't like Musk's shenanigans, so Tesla is off the table. I don't want a Ford or a Chevy; they are truck companies that occasionally make cars. I considered VW but I have ethical concerns supporting the perpetrators of diesel-gate and monkey killing.

There are start-ups making EVs, but I want a company that I know will be around in 5 years for service and parts.

I interjected that there's no guarantee that any company will still be around in 5 years. He agreed but said the bigger companies are more likely to get a bailout if they are in hot water.

I told him that I think he's letting the perfect be the enemy of the good and that any of the above EV choices would be better than continuing to drive a gas car. He agreed, but that didn't help him land on a choice.

A lot of my friends, family, and coworkers know that I'm into EVs and they often consult with me when they are considering an EV. Usually, the questions are about range, charging at home or on the go... He had researched all of that and understood it well. This was a different sort of ideological EV-hesitancy that I haven't encountered before.

His quest for a 'good choice' continues. We'll see which of the "imperfect" vehicles he eventually buys and I'll be sure to let you know here.

Monday, October 3, 2022

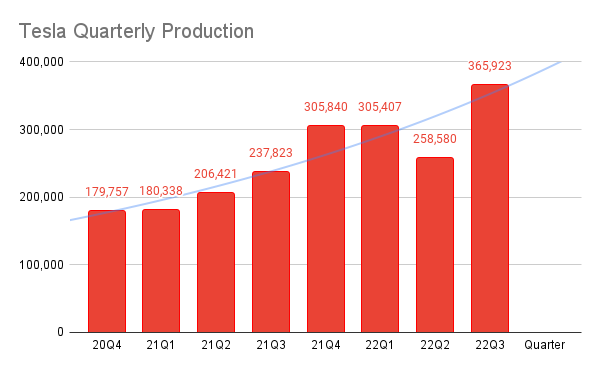

Will Tesla Hit 2 Million Cars in 2022?

2 Million in 2022 has a nice ring to it, but is it possible?

Tesla just released the Q3 production and sales numbers. Sales rose 35% compared to Q2. Giga Shanghai has moved past COVID restrictions and supply chain issues. Even with the significant sales increase, the numbers fell short of some Wall Street estimates.

Sunday, October 2, 2022

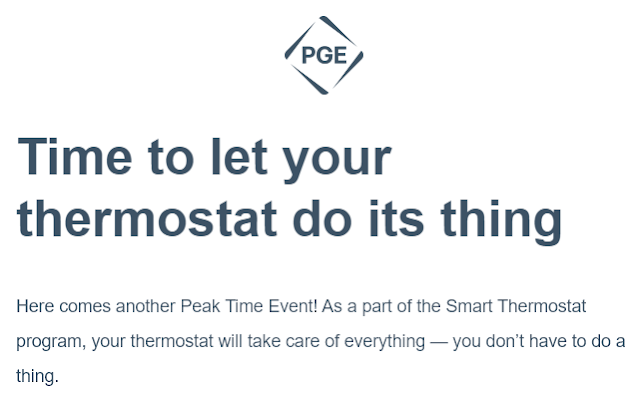

Smart Thermostat vs Smart Battery

Our local electric utility has two programs with similar intentions to reduce grid load during times of high demand. We are participating in both and, sometimes, the two don't really work well together.

Program 1: Energy Rush Hour

Our utility, Portland General, offers a program they call "Energy Rush Hour." This program attempts to alleviate the strain that air conditioning places on the grid during hot summer days.

When people arrive home from work, they typically turn on the AC and with everyone turning on their AC around the same time, the grid load is very high during these hours (4 to 7 PM). Energy Rush Hour reduces this strain by pre-cooling participating homes. Pre-cooling typically starts at 3PM. This means that by 4PM when other homes are turning on their AC, the pre-cooled homes can shut off their AC. This spreads out the load.

If the load wasn't spread out, then the utility might need to use peaker plants to supply the excessive short term energy need. Spreading out the load allows the existing generation infrastructure to fulfill the cooling power demand. Avoiding peaker use is good for the customers, the utility, and the environment. Peaker plants are among the most polluting energy sources and the most expensive source to operate. The cost to run these peakers is certainly passed on to customers in one form or another.

Any month that you participate in an Energy Rush Hour, you receive a $25 incentive bonus on your electricity bill. This more than makes up for an extra electricity use that you may have for having the AC kick on an hour or two early.

So far, so good; let's look at the second program.

Program 2: Home Battery w/ Time-of-Use

By default, residential PGE customers are on a flat rate fee structure. With a flat rate, it does not matter what time of day you use electricity; it's the same cost at 3PM as it is at 3AM. This is convenient since you can run your appliances at anytime of day or night and not get hit with higher fees. However, this default flat rate schedule is blind to the ebb and flow of grid demands.

If you want people to understand something, put a price on it. This is what a Time-of-Use (TOU) rate schedule does. When there's typically surplus supply on the grid (such as overnight), you make the price cheaper to encourage use. And when demand is expected to be high (when hordes of people come home from work and turn on their AC), you make prices higher. PGE's TOU schedule has three rates: peak, mid-peak, and off-peak.

TOU nudges people to push loads into non-peak times. Much like the Energy Rush Hour program, this reduces the demand during peak hours and can avoid or reduce the need for peaker generation.

Where it Goes Wrong - The Interaction -

Ω